Sylvie Verschoote – “Paintings, they have no use other than to please one’s self!”

PONT-DE-BARRET

The Rhône River is the natural dividing line between the Departments of the Ardèche and the Drôme. The landscapes on both sides are very different: to the west a crenulated mountain range runs all along the Ardèche riverbank whereas the Drôme to the east is open country, made up of plains, with here and there low-lying hills, that extend, in the distance, to the Pre-Alps.

The medieval village of Pont-de-Barret (700 inhabitants) at about 30 km east of Montélimar, is situated at the far end of one of these plains, la Plaine de la Valdaine. It is cupped between three mountains, the St. Euphémie, the Eson and the Briesse and built on a hill, topped by a highly conspicuous Romanesque church. With a figment of the imagination, the high facade of Notre Dame de la Brune that was built in the 12th century looks like a ceremonial mitre overlooking the village that tumbles down the slope like so many other picturesque stone villages of la Drôme. Its earliest foundations go as far back as the 9th century, but the main part was developed in the course of the 11th and 12th centuries. The Roubion river flows at the bottom of the village after having passed through a gorge in the mountains and it is crossed by a very old stone bridge from which the village derives its name. This natural passageway probably explains why long ago there was a busy Gallo-Roman settlement here called Savenna. In much later times, during the middle ages, water mills driven by the current served to throw and twist raw silk, a reminder that the Drôme until quite recently raised silkworms on a large scale providing raw material for the famed silk industry of Lyon. The worms were fed with the leaves of mulberry trees that were widely cultivated in the Drôme and there used to be a large number of silk farms called “magnaneries” throughout the Department. Old people today still remember how in many ordinary farmsteads breeding silk worms provided a means for a little extra income. In Pont-de-Barret this thriving textile industry employed about 100 workers up until the 1960s when the development and manufacture of artificial fibres had practically taken over the use of natural ones. The old silk mill building with its high arched windows is still there, but its purpose has undergone a radical change. Interestingly and more to the point as far as this blog is concerned it is now fully dedicated to art! The mill wheels are no longer driven by the waters of the Roubion and the workers no longer reel and thread silk. Instead the buzzing industrial activity has been replaced by creative energy. The premises now accommodate the studios of a well organised group of artists and craftsmen.

The medieval village of Pont-de-Barret (700 inhabitants) at about 30 km east of Montélimar, is situated at the far end of one of these plains, la Plaine de la Valdaine. It is cupped between three mountains, the St. Euphémie, the Eson and the Briesse and built on a hill, topped by a highly conspicuous Romanesque church. With a figment of the imagination, the high facade of Notre Dame de la Brune that was built in the 12th century looks like a ceremonial mitre overlooking the village that tumbles down the slope like so many other picturesque stone villages of la Drôme. Its earliest foundations go as far back as the 9th century, but the main part was developed in the course of the 11th and 12th centuries. The Roubion river flows at the bottom of the village after having passed through a gorge in the mountains and it is crossed by a very old stone bridge from which the village derives its name. This natural passageway probably explains why long ago there was a busy Gallo-Roman settlement here called Savenna. In much later times, during the middle ages, water mills driven by the current served to throw and twist raw silk, a reminder that the Drôme until quite recently raised silkworms on a large scale providing raw material for the famed silk industry of Lyon. The worms were fed with the leaves of mulberry trees that were widely cultivated in the Drôme and there used to be a large number of silk farms called “magnaneries” throughout the Department. Old people today still remember how in many ordinary farmsteads breeding silk worms provided a means for a little extra income. In Pont-de-Barret this thriving textile industry employed about 100 workers up until the 1960s when the development and manufacture of artificial fibres had practically taken over the use of natural ones. The old silk mill building with its high arched windows is still there, but its purpose has undergone a radical change. Interestingly and more to the point as far as this blog is concerned it is now fully dedicated to art! The mill wheels are no longer driven by the waters of the Roubion and the workers no longer reel and thread silk. Instead the buzzing industrial activity has been replaced by creative energy. The premises now accommodate the studios of a well organised group of artists and craftsmen.

It all started in 2004 when Delphine Petit who paints murals and carries out restoration works arrived in Pont-de-Barret and set up shop in the old mill building. At the time a stained-glass artist also lived in the village and both women decided that it would be interesting to form a co-operative. Their initiative paid off well and in time others joined them and set up their studios in the building which is now known as “Le Quai.” Today twenty artists and craftsmen are members of this creative and busy colony of artists. They are painters, ceramists, illustrators, a seamstress, a musician who is also a painter and a clown, a dancer, etc. and although each one works independently, together they develop common activities, organising events and exhibitions that are popular and well attended, making le Pont-de-Barret an artistic hotspot in the Drôme.

SYLVIE VERSCHOOTE

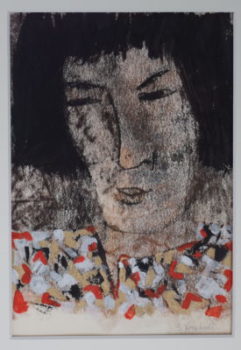

Among the artists to have fallen under the charm of Pont-de-Barret I rediscovered Sylvie Verschoote. The first time I saw her paintings they immediately appealed to me. It was at an exhibition showing a series of high-quality abstract monotypes. In a way, seen from a distance they reminded me of Paul Klee. A closer scrutiny revealed how well assured the composition was and how pleasingly the artist combined her colours, each monotype fully evoking the emotion that had generated it. At least that is how I saw it. Having decided to create this blog Sylvie was one of the artists who immediately sprang to mind. However, it was some years since the exhibition had taken place and I was worried that she might meanwhile have left the Drôme.

Fortunately, this was not the case and I am happy that she has accepted to be this month’s blog post artist.

Sylvie lives at a short distance from Pont-de-Barret proper in a large old farmstead in an open plain fringed by mountains. I contacted her and she invited me to come to see her. As I drove up, I noticed that one of the farm buildings had a small tower which seemed to indicate that the place was once fortified. A couple of other families live on the premises. The part occupied by Sylvie is spacious and comfortable and she has a fair-sized luminous studio, facing north. She welcomed me warmly and as I came in, I noted how the walls were covered with paintings, some unfinished and others she presumably felt needed an extra final touch. There were abstract works alongside realistic still life paintings and spread out on a work bench two portraits of her ancestors she had painted from old time photos. I was impressed by how well Sylvie had mastered the different techniques. Professional artists are often recognised for a particular type of work and stick to one technique for fear of confusing galleries, reviewers and buyers. In today’s consumer society works of art unfortunately tend to be seen as a product and a one and only style a guarantee of quality. These considerations don’t apply to Sylvie Verschoote, quite the contrary!

Sylvie Verschoote has acquired a wide experience by choosing to study in depth and engage in a variety of life experiences. On the one hand, she has an academic background in human sciences and on the other her training in art is 100% self taught. This constitutes an interesting mix that explains her diversity and her conviction that creative artists should make works of art that are close to their hearts and not what is expected of them. But they must do them well!

Each time I asked a question there was a slight delay before she answered as she let my words sink in. In the process of learning her trade by herself, every aspect that proceeds to making art has been well considered and experimented. She seems to be bent on trying out various approaches to a particular technique in order to see if they work. Moreover, she welcomes accidental incidents that lead her up new paths and in so doing she gives a splendid lesson of creativity. I had not expected how well she mastered different techniques. The contrast between her realistic still-lives and the mono-types is striking. You might well wonder whether they were done by the same artist. In the first instance the subject might be classic, simple and straightforward: five yellow pears set before a Prussian blue kettle with an ultramarine background, or three apples, a red one, the other yellow and the third slightly bruised, behind which there is the neck of a vase also painted in Prussian blue. However, the realistic and abstract works do have many things in common. It is always the colour that shapes the subject and determines the composition and the subject also takes up the whole space of the painting. This is also true of the small and spontaneous poetic paintings Sylvie makes of intimate corners of her home. In another series her aim will be to study the variations of the colour blue, etc. This diversity can give rise to a certain amount of scepticism on the part of those who believe that a real artist should express his or herself in one single style as a guarantee of the quality of their work. This standpoint is often upheld by gallery owners and in the art world where too often the work of an artist is considered as a commercial good that is recognisable by its style. Sylvie Verschoote does not take this viewpoint into account and on the contrary goes to prove that creativity expresses itself in a thousand and one ways.

Can you briefly describe the chronology of your life as an artist? When you were a child did you draw? Did your parents encourage you or was it at your own initiative? I know that you did not like going to school but was this also true for drawing classes?

Yes, as a child I often used to draw, together with my year and a half older sister with whom I was very close. My father managed to get hold of excellent Staedler-Noris and Caran d’Ache colour pencils for us of which I still have a few stumps. I also drew the portrait of an adult friend of ours when I was 5 or 6 years old, probably the only one I made when I was so young. My parents were happy that this occupation kept us quiet and so we drew princes and princesses and other fairy tale figures. At school I loved sports, music, drawing, and French classes for I liked writing and words made it possible for me to escape in my mind and travel far away. Other subjects such as arithmetic did not interest me. The truth is that the only times I worked hard at school was when there was a special bond between me and one of my teachers. Otherwise, I reverted to passive resistance. During my adolescence I used to cover my exercise books with drawings of all sorts of funny characters I invented, instead of doing my homework.

You were the youngest sibling in your family and you consequently had to cope with many “chiefs.” How did you react to them? By being secretive, submissive or rebellious?

You were the youngest sibling in your family and you consequently had to cope with many “chiefs.” How did you react to them? By being secretive, submissive or rebellious?

I became secretive in order to protect myself and I was also rebellious. My family adhered to a religious sect of protestant obedience that strictly limited our contacts with the outside world as well as condemning the ways other families lived. I failed to understand why we did not abide by the same rules as others for I wanted to be just like everybody else. Rebelling in order to protect myself and as a means of self-preservation evolved gradually with time. There were all sorts of things we were not allowed to do in our family. Quite apparently this did not apply to others, and this made me feel I was being prevented from leading a normal life. It was unbearable and I thought it was unfair.

How old were you when you left home?

I was seventeen and I traveled a long way away, living in different places where I made heartfelt friends of the people I shared my life with. They were my equals and most of them are my friends to this day.

The need to be independent seems to run like a red thread through your life. Could it be that you want to be recognised for the person you really are, and that’s fine, but is that the reason why you became an artist?

What you say is partly true. I have created a world of my own that shows tolerance. In it there is happiness and harmony and it pursues an ideal of liberty and beauty. This quest for beauty has led me to the visual arts and music. Before, I had been unable to find my place in society but art being a marginal activity it became an opportunity for me to be able to create unhampered by rules. To paraphrase the poet: “And, what might your wound well be?” My wound, beyond any shadow of a doubt, became the driving force that made it possible for me to muster the energy I needed to reconstruct my life.

You studied psychology (perhaps to bring some order in your mind after having lived in incoherence) and you went on to study psycho-linguistics to understand more about how the brain functions (perhaps also to find out why you were different). Finally, you reached the conclusion that the visual language is the best way of stating who you are and what you feel?

The nonverbal language of painting and drawing proved to be perfectly adapted to my need and yearning to express myself openly and in depth. It was a way to live in accordance with who I was and to be the master of my own destiny, no longer as the child who had been manipulated by adults.

When did you become a full-time artist and what is it that determined your choice?

Before I left university I had been given the assignment to write a dissertation on artistic creation for my psychology studies. At the time I had a job to earn a living, but things changed when I was suddenly given notice and found myself unemployed. That was when I decided to take advantage of the situation by stepping backward and spending a few months drawing and painting in a secluded spot in order to find out whether this was to be my life’s path or only a dream. So, I drove off in my little car headed south to the mountains of the Var. I had decided to live sparingly and as close as possible to nature. For instance, armed with a saw and a machete I would go out up into the mountain to collect firewood which I loaded into my car. I knew all the good and bad places in the forest. My life style was elementary, but I soon began to feel at peace with myself and completely at home. A number of people I met at the time (who were painters) confirmed me in my choice. I made lots and lots of drawings and monotypes, often working deep into the night. I really loved the silence of the night!

Listening to you I note how often you use the word “experiment” which is a scientific rather than an emotional approach?

For me to experiment means looking for the right tools and adapting them to what I wish to express. I never had a formal training and so I taught myself by intensively exploring and practicing various techniques in order to find out which ones suited me best. I have always been a loner and so I worked at my monotypes freely, inventing a number of different applications. In literature, I was drawn to the poetical world of the surrealist writers and indirectly they were a source of inspiration: a kind of anchorage and a form of freedom.

You have studied and explored different techniques and considering the results you have managed not only to master them, but they are aesthetically extremely pleasing. You also give painting courses and if I have rightly understood your students are encouraged to express themselves freely. In doing so and in return they teach you a lot which is another way for you of exploring the possibilities of different techniques. You seem to have an urge to get to the very bottom of each technique and that is why you keep passing from one to the other?

I have attempted to get to the core of different techniques as I consider that variety is very important. I love diversity and I want to find it in all things, including in myself. That is why I refuse to let myself be confined to one single way of working. We are many things and we have many facets. Why shouldn’t we show them? There is a saying that appeals to me “I like soup, salad, cheese and the chocolate cake,” and it is always me. It is more like an alternation at a given time, the season, the weather, how I feel or what crosses my mind. Technique only serves to express a prevailing deeper feeling that encompasses everything: nature, the sky, the weather outside, my own moods. They are all constantly interconnected. There are days when some are more perceptible than others and when this occurs, I try to be attuned and in harmony with them. Synchronisation is what I strive to achieve. Technique is the tool required to make things perceptible – even if only for myself – and to testify to the veracity of my deeper feelings.

What in the final analysis gives you more satisfaction, to have mastered a technique and understand how it works or the aesthetic pleasure you derive from what you have created?

There is surely an aesthetic pleasure but for me it is always linked to something deeper. What affects me is when I feel that there is a sort of collusion with an invisible part of myself. It no doubt comes from deeper emotions that live in me and the sense of a bond with the universe.

Posted in: Art