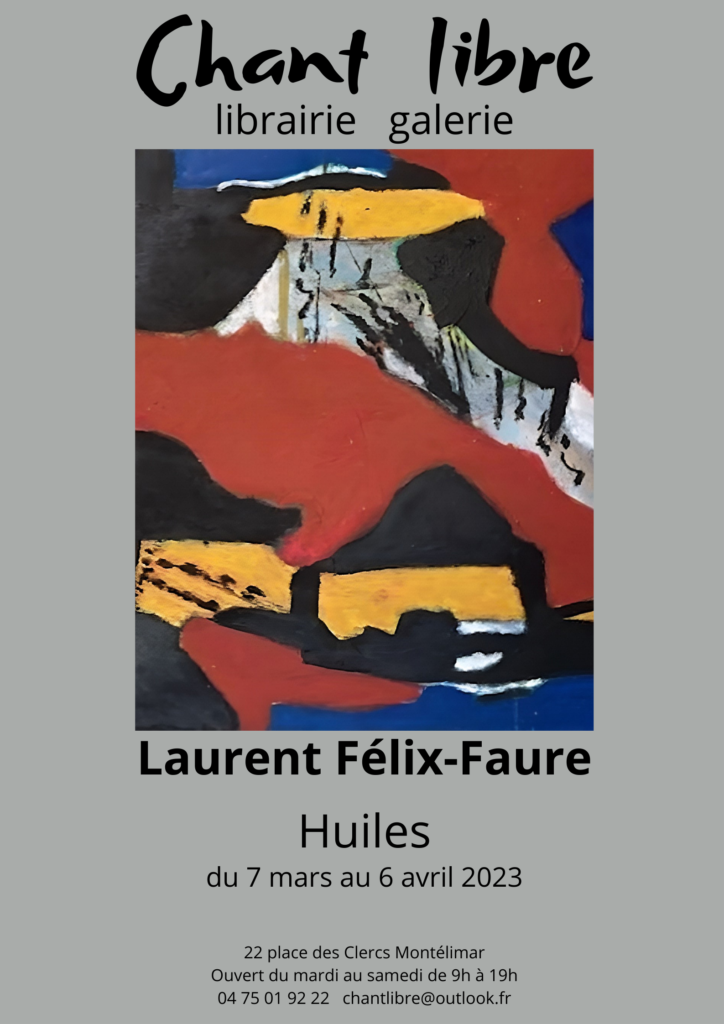

Invitation

From coming 7 March to 6 April I will be exhibiting at the Galerie-Librairie Chant Lire in Montélimar and I would naturally be happy to greet you should you be able to come at the opening. André Zaradski the owner of the gallery expressly asked me to exhibit abstract paintings. For the occasion I have written an illustrated booklet on abstract painting (price 10 €). The present blog contains the text of the booklet and some of the abstract works that go with it in the hope that you might like to read it.

SOME REFLECTIONS ON ABSTRACT PAINTING

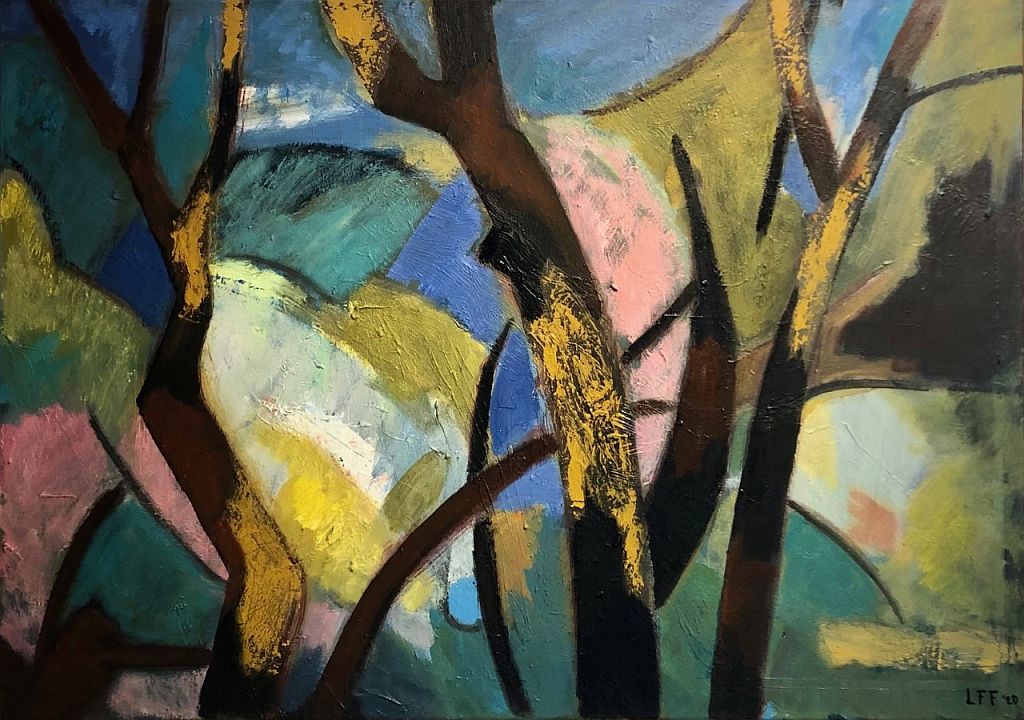

Oil, 60 x 75 cm

A brief return to the past! I must have been five or six years old when I came across a drawing of a sheep in a children’s book. I was completely enthralled. Not so long ago I found the book back and the drawing in an old suitcase. What I had before me had absolutely nothing to do with a sheep; it consisted of a form that looked like a sausage and presumably represented the body of the animal, an oval shape like a rugby ball topped by two triangles at one end and a loop at the other, the whole supported by four matches.

After so many years the drawing still moved me deeply, such is the power of a few lines on paper. I suddenly also realized that by adding a painted background, a few matching colours, the forms and lines in the drawing could be turned into a perfectly acceptable abstract painting. In the case of my sheep, the abstraction was involuntary and due to the lack of talent of the painter. Conversely, proficient artists create abstract works by reducing reality to its simplest expression on purpose. Paintings by Piet Mondrian, a forerunner of modern art, are striking examples. He created many of his works by reducing a tree, a pier jutting out into the sea or a dune into a composition made up of vertical and horizontal lines. Others go by absolute abstraction and refute all references to a visible motif. Serge Poliakoff, whom I like very much avoids titles and calls every abstract painting he makes “Composition”. However, both artists have a common aim and that is to create a visual experience without any reference to exact reality, which is the premise upon which abstract art is based.

Oil, 80 x 100 cm

The discovery of abstract painting in 1913 is attributed to the Russian painter Vassily Kandinsky. It is inseparably linked to contemporary art and over a little more than a century it has been adopted by many renowned artists whose works are worth fortunes on the art market. Although their works fall under various categories such as organic or lyrical, geometric or expressionist nothing in them recalls the real world. For a while abstract art even supplanted figurative painting considered old-fashioned and obsolete in the minds of amateurs as well as for many artists themselves. I can still remember in the seventies how the venerable Royal Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague, where I had enrolled in evening courses, removed life model sessions from the curriculum and stored away its large collection of plaster casts that students in the past painstakingly had to copy.

watercolour, 30 x 40 cm

My first abstract painting was the happy outcome of a failed figurative one. The experience was somewhat similar to that of Kandinsky’s who, so the story goes, discovered abstract painting when he happened to come across one of his landscapes that had inadvertently been hung upside down. All he could see were shapes and colours on the wall, but they dazzled him and made him decide to paint in the same vein. In my case as well, abstraction was unintended. I was struggling with a landscape that lacked something I could not get a handle on. Out of frustration, I wiped away part of what I had painted and to my surprise the result was an almost finished abstract canvas. It met all the required criteria: no subject but only forms, lines and colours; all it needed were a few additional brush strokes and the trick was done. Since then, I don’t try too hard to finish a figurative painting that is not working out. Some have been reconverted into abstract paintings I hold dear!

Oil, 80 x 100 cm

Abstract painting! It is a common name that embraces a vast field of approaches and as far apart as the circular forms of the French painter Robert Delaunay and the meditative, deep-coloured surfaces of the American Mark Rothko, or the rich gestural painting of the German Gerhardt Richter and the poetry in the luminous works of the Chinese Zou Wou-Ki. The list of artists is endless and museums the world over are full of their masterpieces. It would seem that to paint abstract works holds a special appeal that meets the artistic expectations and aspirations of countless painters, including myself. Could it be that a painting being a work of art seen in its entirety the impact is immediate and perhaps stronger when it concerns an abstract painting for there is no subject to divert the attention as for a figurative one? Maybe!

Oil, 50 x 70 cm

I often wonder when I put my brush down after finishing an abstract painting why I feel so happy, and sometimes, but less often, euphoric? Where do the lines, colours and forms I paint that generate such strong emotions come from? It might be wishful thinking, but I am more and more convinced that landscapes are at the basis of all my paintings, whether figurative or abstract? Since I was a child, I have traveled extensively and at a young age I had already resided in a number of different countries, in environments as far apart as the Australian bush and the Norwegian fjords? Each environment left indelible marks, most of them probably unconscious. I also believe that in addition to the physical aspects of a landscape the language used by its inhabitants to describe nature is a verbal transcription of the way they perceive the land they belong to – think of the Inuit Eskimos who have 25 words to detail snow! After each move to a new country, I learned to speak another language to the extent of speaking it like the local inhabitants and sharing their way of expressing their perception of various aspects of the landscape.

Oil, 40 x 50 cm

I believe that my abstract paintings are fragmented remembrances of all these places where I have lived: a sharp mountain ridge once seen, the golden colour of wheat fields, the metallic reflections of the North Sea or the blue of the Pacific, winding rivers, the geometric lines of polders, those low-lying tracts of land reclaimed by the Dutch from the sea. Should we then speak of geographical abstraction?

Watercolour, 40 x 30 cm

Each artist has his own approach. For me, a few spots of colour, randomly scribbled lines, a form or two on canvas suffice to start making an abstract painting. There should be nothing to remind me of an existing motif or concept, and no preconceived ideas. I haven’t the faintest idea where I am heading to and I stall thinking about a final result as long as I possibly can. Paint brush in hand, as I proceed, colours and shapes follow one after the other until I perceive the outlines of a composition. Here caution is required. I must resist the temptation to round things off which would imply using my rational mind. Better go on as before in order to ensure spontaneity. The work must be instinctive, dictated by the subconscious as long as possible. At the beginning my efforts frequently ended up in failure, either because I was impatient or through lack of concentration. Today, experience helps me to work more continuously. The moment I conclude that a painting is finished comes when I am convinced that there is nothing more to be added. Although I like sketching people and enjoy painting figurative subjects, my abstract paintings are the ones that give me a real sense of freedom and stir up the strongest emotions.

And, if it is true that paintings reveal the inner personality of an artist by the way the composition is handled, the choice of colours, the assurance or the weakness of the brush strokes, I leave it to others to imagine – and judge if necessary – who I am. For my part, I can only say that my abstract paintings speak to me and surprise me by arousing sensations that I carry close to my heart.

Posted in: Art