Benjamin Royaards (1939-2009) – A Genuine Artist

MONTBRISON-SUR-LEZ

The main road (D538) from Dieulefit heading south begins by winding up the mountain and then down again on the other side to the narrow and spectacular gorge of the Lez river. On the right-hand side towering craggy rocks reveal a striking pattern of variegated geological strata. The road follows the meandering course of the river and comes out onto an altogether different landscape. The temperature goes up slightly, the light is sharper and casts more clearly defined shadows, as though they had been added by a painter’s brush. The countryside flattens out and on both sides of the road long braided rows of vines and silvery olive trees cover vast stretches of land. This is where the Provence really begins! To the east culminating at 1300 meters the drawn-out mountain range of the Lance hovers above the plain. Montbrison-sur-Lez is one of the villages at its foot. There are a number of old stone houses in its centre, an 11th century chapel that was rebuilt in the 15th century and the “memory” of other buildings that go back to the days when the region was part of the Roman Empire. The 300 inhabitants of Montbrison-sur-Lez are mostly spread out over the surrounding area, like Katrijn, Benjamin Royaards’ widow who has continued to live in their large farmhouse, 2 kilometres further up on the road to Valréas.

For those who are interested in prehistoric times, the site on which the Montbrison-sur-Lez is built is unique as relatively recent excavations have testified to age-old human presence. In 1954 in the village of Le Pègue, a stone’s throw away from Montbrison, “curious pottery work” was dug up by the builder of a new school. A surprising array of painted pottery was also found in a badger’s burrow at the foot of an oak tree. Further investigations on a nearby triangular hillock led to the discovery of a Celtic Opidum. The excavations that followed also revealed vestiges dating as far back as 5 to 6000 years. The Celts, or Gauls, settled here six centuries before our era establishing a flourishing barter trade with the Greeks who founded Massiglia or Marseille at about the same time. The latter brought wine and olive oil, introduced perfumes and ceramics that they exchanged against amber, metals, wheat and other grains. Today, in the little museum of le Pègue an extremely interesting collection of archaeological artefacts retraces this past. Among them there are deeply moving objects on show like the pots containing the charred remains of wheat that had presumably been stored for trading purposes. Viewing them, far away times suddenly appear to be very close-up for they evoke harvests to feed human beings who were not different to us, except that they lived 2000 years ago. A detour via le Pègue before or after having visited the studio of Benjamin Royaards studio (see below) is more than worth the detour.

BENJAMIN ROYAARDS (website)

Following the example of several well-known Dutch painters such as Jongkind, Van Gogh, Van Dongen and many others, Benjamin Royaards left his homeland with his family and moved to France where he settled in Montbrison-sur-Lez in the Drôme. He lived there for the next 34 years up until his death in 2009. It is also where he carried out the greater part of a remarkable and varied body of work that clearly bears the mark of a significant artist.

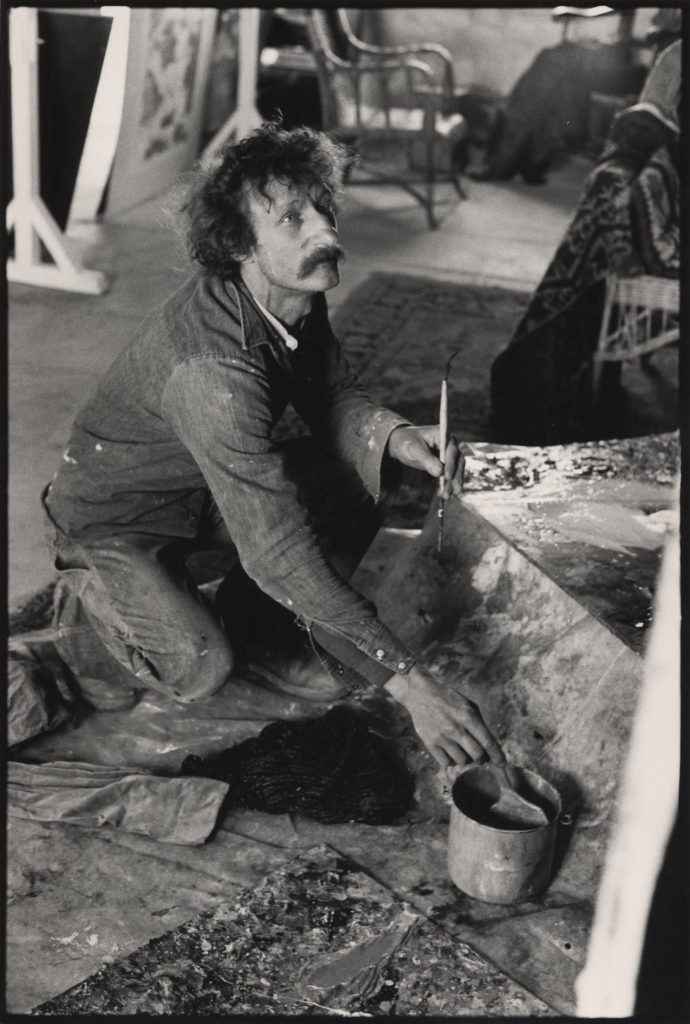

His talent was discovered at the early age of 19 while he was still a student at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam and this led among other things to a commission by the City Council to paint the frescoes of the Royal Palace on the Dam. He also took part in many important events obtaining an award at the International Art Fair of Monaco, a first prize of the Biénnale de gravure de Digne in France (1982), further exhibiting at the Grand Palais in Paris, etc. It was partly in order to avoid the pressure and the obligations that resulted from his success that Benjamin decided to leave Holland and dedicate himself fully to his art work without being disturbed. From that time onwards gallery owners and art lovers from many countries, from Holland, Belgium, Germany, the US, etc., travelled all the way to Montbrison to visit him. They were warmly welcomed by a highly colourful character who jokingly liked to compare himself to Don Quixote, the hero of Cervantes. And indeed, Benjamin’s sinewy physique, the sharp features with the prominent nose and the piercing blue eyes do bear a resemblance to the proud knight of la Mancha. There is also something of the same fiery spirit in his work. The paintings, figurative or abstract, large or small, the sculptures carved in the stones he retrieved from the bed of the neighbouring Lez river, the surprising forms of his ceramics, all testify to a joyous expressionistic art that comes from the heart. So was the man, so was the artist!

His talent was discovered at the early age of 19 while he was still a student at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam and this led among other things to a commission by the City Council to paint the frescoes of the Royal Palace on the Dam. He also took part in many important events obtaining an award at the International Art Fair of Monaco, a first prize of the Biénnale de gravure de Digne in France (1982), further exhibiting at the Grand Palais in Paris, etc. It was partly in order to avoid the pressure and the obligations that resulted from his success that Benjamin decided to leave Holland and dedicate himself fully to his art work without being disturbed. From that time onwards gallery owners and art lovers from many countries, from Holland, Belgium, Germany, the US, etc., travelled all the way to Montbrison to visit him. They were warmly welcomed by a highly colourful character who jokingly liked to compare himself to Don Quixote, the hero of Cervantes. And indeed, Benjamin’s sinewy physique, the sharp features with the prominent nose and the piercing blue eyes do bear a resemblance to the proud knight of la Mancha. There is also something of the same fiery spirit in his work. The paintings, figurative or abstract, large or small, the sculptures carved in the stones he retrieved from the bed of the neighbouring Lez river, the surprising forms of his ceramics, all testify to a joyous expressionistic art that comes from the heart. So was the man, so was the artist!

Click on the image to watch a wonderful short documentary on this unique artist.

Click on the image to watch a wonderful short documentary on this unique artist.

Paintings

Benjamin Royaards was an artist, heart and soul and he mastered every painting technique to perfection: oils, gouache, watercolour, pastel. He favoured subjects that were close to his home, scenes from daily life, portraits of the members of his family who were his models and the landscapes of the Drôme, the region they had chosen to live in. The paintings he made are harmonious and pleasing to the eye. However, they are far from being simply decorative for he worked in depth. Although Benjamin was firmly anchored in his times, his roots were those of a painter from the North of Europe, heir to Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Jan Steen in the 17th century and of Jongkind, Van Gogh, Van Dongen at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century for whom content is considered just as important as form. He excelled as a colourist and in his vast studio there was an impressive array of pots containing pigments that he selected and mixed in order to achieve the right hues and the desired intensity of colour judged appropriate for the painting he was working on. Benjamin always insisted that all his paintings – even the most abstracted ones – were based on reality. As for his portraits, the self-portraits, those of his wife Katrijn and their children, and even those of his dog, they all radiate life with a touch of humour and a great deal of tenderness to boot.

Benjamin Royaards was an artist, heart and soul and he mastered every painting technique to perfection: oils, gouache, watercolour, pastel. He favoured subjects that were close to his home, scenes from daily life, portraits of the members of his family who were his models and the landscapes of the Drôme, the region they had chosen to live in. The paintings he made are harmonious and pleasing to the eye. However, they are far from being simply decorative for he worked in depth. Although Benjamin was firmly anchored in his times, his roots were those of a painter from the North of Europe, heir to Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Jan Steen in the 17th century and of Jongkind, Van Gogh, Van Dongen at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century for whom content is considered just as important as form. He excelled as a colourist and in his vast studio there was an impressive array of pots containing pigments that he selected and mixed in order to achieve the right hues and the desired intensity of colour judged appropriate for the painting he was working on. Benjamin always insisted that all his paintings – even the most abstracted ones – were based on reality. As for his portraits, the self-portraits, those of his wife Katrijn and their children, and even those of his dog, they all radiate life with a touch of humour and a great deal of tenderness to boot.

Drawings and Prints

Considering the vast number of drawings and sketches left behind by Benjamin it is reasonable to assume that for him it was a non-stop way of telling about his daily meetings with people and of describing the events and happenings that had caught his imagination. The drawing pads that still pile up in boxes in his studio today are magical logbooks that testify to a sure hand that unfailingly grasps the essentials. There is no other word than superb to describe the many large and detailed sanguine drawings of Amsterdam where he resided as well as those around Montbrison. As for the dry point prints – even if it may sound slightly overstated – the comparison can be made with his fellow countrymen Rembrandt and Hercules Seghers. Aquatints hold a prominent place in Benjamin’s body of work and it is a technique that particularly suits his generous and spontaneous style.

Sculptures, ceramics and other objects

Sculptures

It is after having moved to France that Benjamin took up sculpture. Owing to the centuries-long erosion of the river stones carried by the Lez river near to his home they sometimes resemble rough shaped sculptures. A good enough reason for Benjamin to want to complete the work, and so he turned to his friend the sculptor Theo Mulder who went on to teach him the basics of his craft. With his customary zeal Benjamin set to carve stones. It was not an easy undertaking as river stones are extremely hard and more than once his inexperience caused him to suffer sharp pains in his arms and shoulders. Although they are less numerous than his paintings, the sculptures do however constitute an integral part of Benjamin’s oeuvre.

Ceramics and other objects

Benjamin’s love of ceramics began at an early age when he took part in excavations in the North of Holland and found beautiful fragments of Majolica earthenware dating back to the 17th century. Completely taken in by this discovery he would later decide to follow an apprenticeship at the Royal Tichelaar Pottery Company that was reputed for its earthenware. In Montbrison, Benjamin built a large wood-burning furnace with his own hands and started creating unusual, well-turned and multi-coloured ceramics, experimenting with different combinations of materials, even introducing iron into his clay.

Benjamin’s love of ceramics began at an early age when he took part in excavations in the North of Holland and found beautiful fragments of Majolica earthenware dating back to the 17th century. Completely taken in by this discovery he would later decide to follow an apprenticeship at the Royal Tichelaar Pottery Company that was reputed for its earthenware. In Montbrison, Benjamin built a large wood-burning furnace with his own hands and started creating unusual, well-turned and multi-coloured ceramics, experimenting with different combinations of materials, even introducing iron into his clay.

This inborn drive to transform objects and turn them into works of art, made up of heterogeneous materials, pushed Benjamin to spend hours nosing around in the local waste collection dump. He also tried his hand at papier-mâché in order to make raised design art, built a” poetical” carrousel, an “aquarium-cupboard” with fish he cut out of aluminium foil, a fantasy circus, etc, etc.

Summing up, what stands out when one stops to consider Benjamin’s oeuvre as a whole is how wide-ranging it is, its exceptional aesthetical quality and his command of the technique whatever the medium he chose to work in.

Benjamin Royaards at work

Posted in: Art