Sylvain Canaux

“High up above, the bird soars

Sitting on a branch, it chirps

Resting on my windowsill, it sings

Cupped in my hand, it talks

The wingless bird on my table, questions me!”

(Régine Canaux)

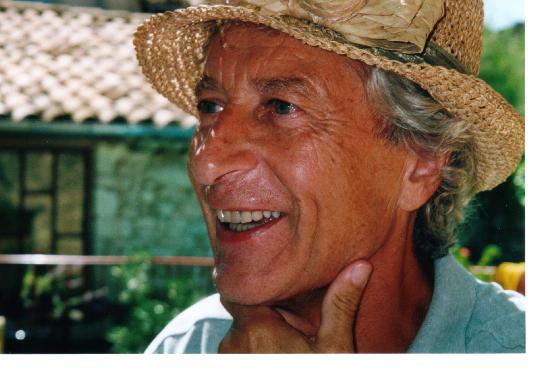

This month’s blog post pays tribute to an artist who was my best friend in Dieulefit. Sylvain Canaux died 4 years ago. I miss him and the times we spent together talking about art and many other things for he had a wide range of interests. Like many genuinely talented figures he was discreet and modest. I can still clearly see him – not one to claim attention – a tall and elegant figure with clear blue eyes and a somewhat dreamy look, quietly observing his surroundings. It might come as a surprise but our friendship began with basketball. We were both long past the age of being players but we had been ones, he I must admit at a higher level than me. We also quickly discovered that we had many common views and that we both shared a passion for art which was to become an unending source of conversations between us. On two occasions we even exhibited together!

Sylvain’s first steps as a sculptor came late in life. In essence he was always an artist and a creative personality heart and soul. His path reads like a meandering river through a great diversity of landscapes in which he encountered and worked with some of the most colourful figures in the arts of his time. He spent hours interviewing and joking with the ageing pianist Arthur Rubenstein who was full of humour, at his Parisian home on the Butte Montmartre. Rostropovich with his Cello climbed the three flights of stairs that led to the office of “Musique” a music magazine Sylvain ran with two colleagues, surprising them with an impromptu performance to show his appreciation for an article they had written about him. Sylvain also wrote a book on the famous German soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf while mixing with the Paris literary and artistic circles, visiting sculptors like César and a host of other painters at their studios, among whom Raymond Moretti, whose work he particularly appreciated… But let me begin at the beginning.

Sylvain came from an artistic family from which he presumably inherited his talent and who influenced his perception of the world around him. His father was a pianist who had studied applied arts and his mother a violin teacher. They entertained friends who were professional and semi-professional opera singers with whom they held music sessions at their home. Growing up in surroundings immersed in classical music, Sylvain who was young and also had an ear for music wanted something else. It was during the years that Saint-Germain-des-Prés had become the hotspot for jazz and be-bop. With his band of friends he visited the small jazz clubs and the cramped smoke-filled cellars admiring the swirling dancers – many of whom were black American soldiers who had stayed on in Paris after the war – led by emblematic jazzmen such as the clarinettists Sydney Bechet and Claude Luter, the trumpet player Boris Vian and others. At the same time, Sylvain moved around in the Parisian art circles that would later determine his professional orientation. When the time came to pursue his studies he opted for architecture but having realised after a year that this was not his cup of tea he enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the Academy of Fine Arts, a choice that was far better suited to his nature. It is also interesting to note that Sylvain was an accomplished sportsman. I read somewhere – but I might have misunderstood – that artists and sportsmen often have the same sort of visual capacities and a similar sensory motor control! Be that as it may, Sylvain excelled in a variety of sports and above all he was a top basket ball player – which as I have already mentioned is how we got to know each other in the first place.

Sylvain came from an artistic family from which he presumably inherited his talent and who influenced his perception of the world around him. His father was a pianist who had studied applied arts and his mother a violin teacher. They entertained friends who were professional and semi-professional opera singers with whom they held music sessions at their home. Growing up in surroundings immersed in classical music, Sylvain who was young and also had an ear for music wanted something else. It was during the years that Saint-Germain-des-Prés had become the hotspot for jazz and be-bop. With his band of friends he visited the small jazz clubs and the cramped smoke-filled cellars admiring the swirling dancers – many of whom were black American soldiers who had stayed on in Paris after the war – led by emblematic jazzmen such as the clarinettists Sydney Bechet and Claude Luter, the trumpet player Boris Vian and others. At the same time, Sylvain moved around in the Parisian art circles that would later determine his professional orientation. When the time came to pursue his studies he opted for architecture but having realised after a year that this was not his cup of tea he enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the Academy of Fine Arts, a choice that was far better suited to his nature. It is also interesting to note that Sylvain was an accomplished sportsman. I read somewhere – but I might have misunderstood – that artists and sportsmen often have the same sort of visual capacities and a similar sensory motor control! Be that as it may, Sylvain excelled in a variety of sports and above all he was a top basket ball player – which as I have already mentioned is how we got to know each other in the first place.

Having obtained his degree Sylvain found a job in an advertising agency doing graphic work and although he was still in his early twenties he was given the task of stand-in for the art director of the daily France Soir. From then on the accumulation of his activities is slightly dizzying. Contracts followed in quick succession. He became the art director of a magazine dedicated to architecture that had been set up by Jean-Louis Servan Schreiber. The Havas Group one of the largest communications and press bureaus in the world availed themselves of his services and Elle Magazine appointed him as their art director, a prime position he held for two years. However, his most challenging professional adventure came when he was asked to breathe new life into a magazine called Vital that was on the decline, a task into which he put his whole heart, considerably boosting its readership. For 10 years he acted as its art director and international reporter travelling the world accompanied by a stylist, a hairdresser and fashion models who were photographed on location for the fashion page of the journal. Finally, from 1991 to 1996 (the age of his retirement) he was the art director and editor in chief of the well known French weekly Le Point for whom he had previously set up the magazine “Musique” (I have already mentioned Rostropovich’s visit to its editorial staff!).It is therefore hardly surprising considering his highly active and multifarious career in the fields of art and the press that Sylvain came to be known as “The Visual Journalist.”

Having obtained his degree Sylvain found a job in an advertising agency doing graphic work and although he was still in his early twenties he was given the task of stand-in for the art director of the daily France Soir. From then on the accumulation of his activities is slightly dizzying. Contracts followed in quick succession. He became the art director of a magazine dedicated to architecture that had been set up by Jean-Louis Servan Schreiber. The Havas Group one of the largest communications and press bureaus in the world availed themselves of his services and Elle Magazine appointed him as their art director, a prime position he held for two years. However, his most challenging professional adventure came when he was asked to breathe new life into a magazine called Vital that was on the decline, a task into which he put his whole heart, considerably boosting its readership. For 10 years he acted as its art director and international reporter travelling the world accompanied by a stylist, a hairdresser and fashion models who were photographed on location for the fashion page of the journal. Finally, from 1991 to 1996 (the age of his retirement) he was the art director and editor in chief of the well known French weekly Le Point for whom he had previously set up the magazine “Musique” (I have already mentioned Rostropovich’s visit to its editorial staff!).It is therefore hardly surprising considering his highly active and multifarious career in the fields of art and the press that Sylvain came to be known as “The Visual Journalist.”

It is well known that people who have lived busy and rewarding professional lives are not content to sit back doing nothing when they retire. Sylvain and his wife Régine who had run a gallery exhibiting glass art in Paris and shared his passion for art decided to move further down south. They finally landed in the Drôme where after having hesitated between Grignan and Dieulefit they opted for the latter. It is then that Sylvain who had designed hundreds of brochures, magazine covers, posters and publicity material unexpectedly discovered the art form by which he could express himself fully and would prove to be a continuing source of satisfaction for him up to the end of his days. He became a sculptor. Before long he held an extremely successful solo exhibition in Paris during which, much to his astonishment, practically all the works were sold. Other exhibitions followed in Paris and in the Drôme, notably on two occasions at the Galerie Emiliani, with glowing reviews of his work.

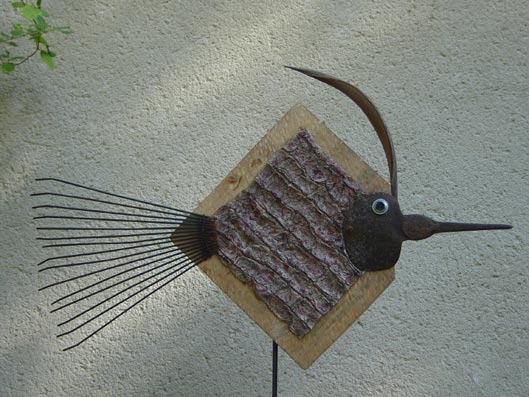

Sylvains’s very first sculpture was made out of a log slab, a beautifully carved round-bellied fish. My friend H who is sceptical about modern art would probably have commented: “But why does a grown up man of his age make a thing like that, and call it a fish? Fish aren’t like that, he should know better!” Well of course the sculpture doesn’t resemble the fish that swim in the sea and are sold at the market for Sylvain was an artist and a poet who left the world of reason behind him in return for the world of his inner-self and of creativity. Coming after the fish Sylvain made sculptures of peculiar birds and curious human figures. I imagine the fun he must have had, putting together these extraordinary, touching and slightly comical beings made out of all matter of bizarre components.

Sylvains’s very first sculpture was made out of a log slab, a beautifully carved round-bellied fish. My friend H who is sceptical about modern art would probably have commented: “But why does a grown up man of his age make a thing like that, and call it a fish? Fish aren’t like that, he should know better!” Well of course the sculpture doesn’t resemble the fish that swim in the sea and are sold at the market for Sylvain was an artist and a poet who left the world of reason behind him in return for the world of his inner-self and of creativity. Coming after the fish Sylvain made sculptures of peculiar birds and curious human figures. I imagine the fun he must have had, putting together these extraordinary, touching and slightly comical beings made out of all matter of bizarre components.

It is interesting to read how some reviewers have expressed their admiration as well as their surprise on discovering the originality of Sylvain’s art. The following comments show just how these assessments differ from how art critics usually write about art:

“Sylvain Canaux’s sculptures take on forms that nature has either refused to be responsible for or has kept safely to itself;”

“It is like taking a walk in a future world where birds and not apes have replaced human beings;”

“Sylvain Canaux or the art of pulling tools that have long been cast aside out of their oblivion and recasting them into part-birds, part- fish, part- human beings* who wear surprised questioning looks as though they are asking themselves who am I and what am I doing here? To which Sylvain’s answer seems to be: whoever you are, you are not here to be criticized and blamed but to make us happy and laugh.”

I often visited Sylvain in his studio in Dieulefit that was a real Ali Baba’s cave for artists, stacked with an incredibly rich collection of paraphernalia ranging from brooms, hat racks, forks, grain shovels, whole sets of tools from bygone days, dried algae and even a large beehive – he had found I believe in Normandy – made of cow dung. Those were the components with which he created his sculptures, calling them “mioiseaux, mipoissons, mihommes*.” I have one in my study, her name is Antonia and when I look at her she waves back at me, and I think of Sylvain.

For more ample information, please contact: reginecanaux@orange.fr

Posted in: Art