Nathasha Krenbol – Curiosity about “elsewheres”

Le Dagda dieu-druide dit Ruadh Rofhessa rouge de la grande science 25×33,5cm

Words fail to express why Natasha Krenbol’s paintings appeal to me so strongly. When I first saw them, they immediately stirred deep-rooted unspoken feelings that live inside me. I generally don’t have much trouble in explaining why I like or dislike a painting. It can be a matter of form, the colours, the composition, the subject matter. In this case however, apart from my enthusiasm all I could do in trying to understand why her paintings speak to me was to find out a bit more about Natasha’s artistic path, read the reviews and critiques that have been written about her work and ask questions by interviewing her. To illustrate how her work affected me, I can recall having the same kind of shock some years ago when I stopped dead in my tracks on seeing a painting in the museum of Grenoble that filled me with surprise and wonder. I went back a number of times in order to soak up every last bit of it. I am unable to describe what the painting represented but to this day its sheer force and completeness remain crystal clear in my mind. Could his be the secret of art? But back to Natasha Krenbol. I discovered her work when she held an exhibition at the Library-Gallery Chant Libre in Montélimar last April following my own exhibition. I happened to be present when a large parcel arrived containing one of her paintings. André Zaradski who is the owner of the gallery started to open it but before he had finished unpacking and on seeing only part of the contents I was hooked.

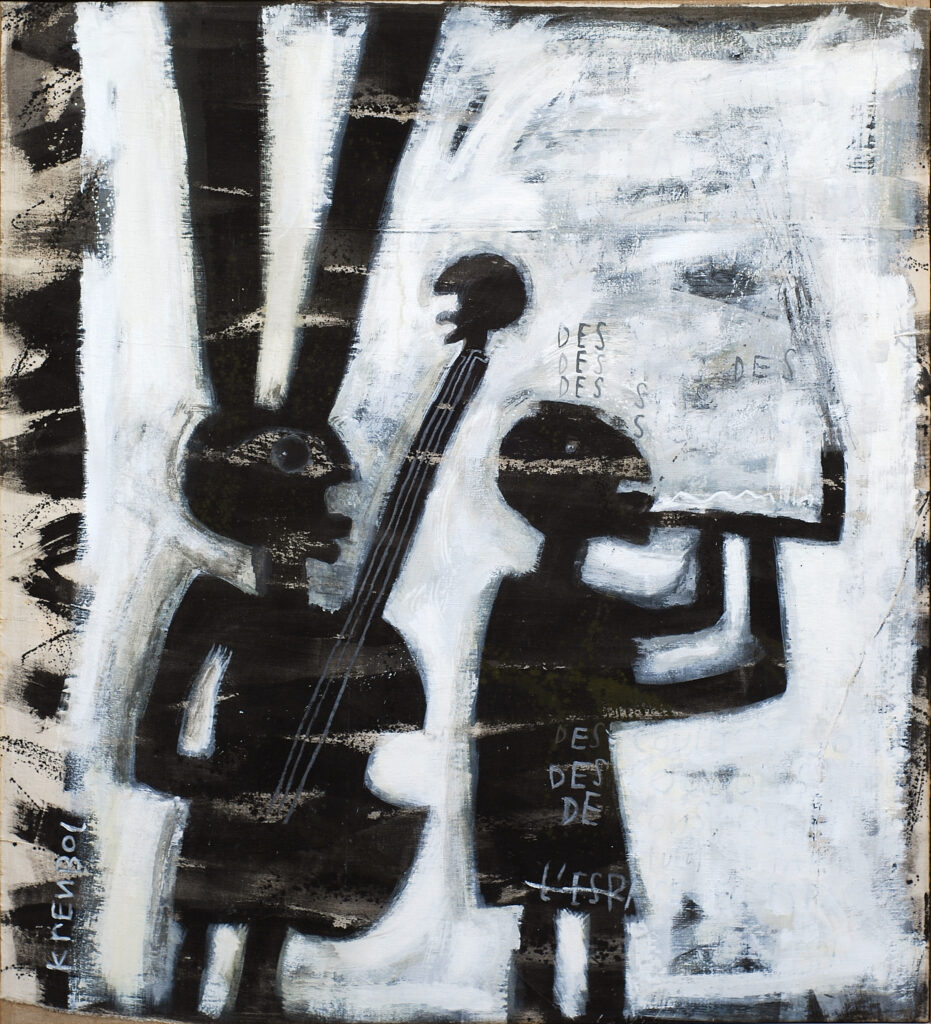

Chechnya blues, 65x54cm

Natasha clearly draws her inspiration from a multitude of sources. With an economy of means and a simplicity of expression her art has a universal character that goes straight to the heart of things. It reminds me in some respects of the Cobra movement and of Art brut or Naïve Art. Jean Dubuffet is just around the corner as well as the poetical subtilities of Paul Klee’s graphic art. Nowadays, the Dutch contemporary artist Charlotte Schleiffert makes paintings which, like hers, represent imagined figures that are partly human, partly animal and partly vegetal. Although there are undoubtably more comparisons to be made, the freshness in particular of Natasha’s paintings, spontaneously made me think of those of the African-American painter Bill Traylor, who was born into slavery in the State of Alabama. In his paintings I see the same humorous vision of humanity, movement so full of life (nothing is static) and each one tells a story, all combined in a simple childlike way. However, unlike Bill Traylor who was self-taught, Natasha has benefitted from a high-level academic training at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and at the Kala Institute in Berkeley in California. In the course of the years she can look back on a long line of exhibitions both solo and collective in France and abroad.

Nouvelles aurores, 19.6×24.5cm

Natasha is a world traveller who passes from one culture to another all the while observing her fellow human beings and the angels and demons that inhabit them. Her work incorporates elements of folklore, mythology, and ethnography. Tribal art frequently occupies a significant place and it is remarkable how well she manages to imbue all things with mystery in her compositions. In reviews about her art the term animism is often used, thereby suggesting that Natasha believes there are spirits in people, animals, plants and in inert matter. Nothing is unimportant!

I am not an expert nor an art critic who seeks to analyse and explain the work of an artist, but an “amoureux”, an art lover. For me, art is a source of beauty, dreams, reflection and joy, but also at times of disgust and even repulsion. When I look at a painting, I sometimes have a better understanding of what illuminates or darkens our existence as well as getting a glimpse of the forces that motivate the behaviour of my fellow human beings. Natasha Krenbol’s paintings reflect (EUREKA!) my travels, my multicultural roots and my own life experience… her work is clearly that of a significant artist.

I was curious to know more about Natasha herself and her position in life as an artist. She has kindly agreed to answer the following questions concerning her background and her reasons for making art.

Question

The art you make obviously draws from a variety of sources. When I look at your paintings the word “elsewhere” comes to mind. Am I right ?

From Egypt to Gaza,120x120cm

Answer

« What would I do without this silence, an abyss of murmurs” *

Samuel Beckett, Poem 1948

You are quite right, my family comes from “elsewhere” but I don’t know that my art has any anything to do with my forebears. My father was born and raised in Egypt where he grew up. My mother spent her adolescence in Zurich. She was inspired by the Dada movement, she was a diligent pianist and a regular at the Schauspielhaus, the main theatre in Zurich. As long as I can remember I have always been interested in others, about what goes on elsewhere, about other ways of life, eating habits, dance customs… But I am also fascinated by the animal world (including insects) which I have always loved. I was a rather solitary child but I was never bored. I remember all my friends, the crickets, lizards, fireflies and the dogs (the latter belonged to our neighbours as my parents refused to have pets in our apartment – except of caged birds that kep me company during my frequent convalescences).

Les chats sont des hommes comme les autres, 46x38cm

The feeling of proximity with the animal world and in a broader sense with nature in general has always remained. At the end of my adolescence, which was chaotic to say the least, I longed for liberty and to discover the world. So I took off and spent the next ten years in Africa and in the United States.

As a child I loved to paint and make drawings that told stories, like children all over the world. I used to make objects out of pieces of fabric, bits of cardboard, twigs, etc. When I was still very young, I remember looking at reproductions of Paul Klee’s paintings which intrigued me because they were strange and so well balanced as well as those by Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Breughel the Elder. Having said this I cannot remember ever having “decided” to become a painter. It just happened and to paraphrase Samuel Beckett’s answer to a journalist who asked him why he wrote: because “it was the only thing I was good at”. *

Question

You are a passionate music lover and you were a dancer. How does that influence your work as a painter?

Triomphantes vibrations, 121x109cm

Answer

Music is important in my life especially the jazz scene of the sixties: Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Duke Ellington, Chet Baker, Abdullah Ibrahim, Pharoah Sanders, Abbey Lincoln, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Andy Bey, Branford and Winton Marsalis…. but also, Debussy, Bach, Ravel, Schubert, Satie and traditional music from all non-Western countries, those of Africa, the Maghreb, Japan, the Caribbean. It would be difficult to explain the effect of music on me and on my painting. You could perhaps speak of changing gears and that music triggers off and communicates its energy to me.

Straight up and down, 118x108cm

I feel that everything in my life tends toward art. This is true of my garden, for what I eat, of what I look at…my eyes are constantly on the alert. This state of vigilance can be painful when at times I am confronted with the objective ugliness produced by Homo industrialis.

Question

If you were asked whether your art is autobiographical, socially engaged or simply art for art’s sake what would your answer be?

Answer

My painting is not autobiographical as such. I would like to be able to say that I am socially and politically engaged but is not up to me to decide. It is up to the viewer to decide. As Dubuffet says: “A salad itself is not in a position to decide whether it belongs in the category of salads or not.” *

Question

Why make art and is it useful ?

Façons d’endormi, 45x64cm

Answer

We have recently seen how fossil fuel companies, the main perpetrators of global warming, have reneged on their climate “commitments. Extreme capitalism continues to swamp us with petrol, gas and coal as if nothing is wrong and to increase their profits. With the world in flames and prey to the greed of a small group of persons, art is an absolute necessity, even if, as for love and poetry, it has no tangible value. But it propels us forward, it nourishes us and it heightens our humanity. It gives us the opportunity to show concern for the human side of life and for what transcends the human . The place occupied by money is revolting, deadly and irrational; It disturbs the human fusion with the soul – the utopian powers. Art is a questioning form of meditation in a context of cynical and calculating logic. He dreams “aloud” of the day when the word human will become the equivalent of sapiens…

Question

There are about 60.000 registered visual artists in France today and only some 2000 well established galleries. How does a visual artist manage to make a living in these circumstances?

Answer

C’est ainsi, 32x32cm

I never planned to make a career. I have had extremely successful periods working in cooperation with capable dealers – especially in Switzerland, in Chicago and elsewhere in the United States…When I was younger, I was criticised for being young, for being a woman and for making “men’s” paintings… Today, gallery owners prefer young artists and the situation is reversed. But no need to panic! As my grandmother used to say, the first eighty years in art are the most difficult one’s…so there is hope. It is true that there are many visual artists and few good and trustworthy gallery owners and that this has led to a disastrous sort of bottleneck. I am fortunate that I have a number of loyal collectors who support me.

Question

Aside from oil painting what other techniques do you like?

Answer

Watercolour. I mainly use acrylics and pigments, colour pencils and pastels, both dry and oil. I also like to make assemblages with unusual things I find on my walks, which become kinds of curio cabinets, theatre stages with all kinds of characters.

Question

What inspires you?

Answer

I feel close to my childhood as well as to the Chinese painters. The statements of Shitao known as “Monk Bitter Gourd” in a treatise from the XVIIIth century are a constant source of inspiration for me.

“When man is blinded by things, he commits himself to dust. Man’s heart is troubled when he lets himself be dominated by things. A troubled heart can only produce laboured and rigid paintings that lead to their own destruction. Therefore, I let things follow the course of their obscurity and dust commit itself to dust; thus, shall my heart remain untroubled. For when the heart is untroubled painting can be born.”*

Pavane, 120x120cm

Website: http://www.natasha-krenbol.fr/index_en.html

*All quotes are free translations from French.

Posted in: Art